As an author, I’m always excited when an academic wants to talk about my work. A reader’s review on a bookseller’s website—good; an article by a knowledgeable reviewer—even better; but the analysis of an academic bringing the weight of an entire conceptual framework and the context of your literary canon? That’s something else entirely. Writers can spend a lot of time scrutinising their trees right down to bark texture and leaf shape, so when someone on the outside tells them ‘by the way, did you know your forest looks like this’, it can feel like an epiphany.

That was my experience late last year, when I was interviewed by Dr Brian Alleyne, senior lecturer in sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London. He began by introducing the concept of the sociological imagination, which ‘enables its possessor to understand the larger historical scene in terms of its meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals’ (C.W. Mills 1959, The Sociological Imagination, p. 5). Did I consider my fiction to be a product of a sociological imagination, where private troubles, public issues, and historical context were considered through overlapping lenses of biography, sociology and history? Why yes, I certainly did! Suddenly it all made sense—why my characters moved indiscriminately in and out of the spotlight; why my settings contained enough detail to complicate, but never fully explain; and why my plots were more likely to come full circle than see full victory.

I believe Midtopia is the natural setting for sociological fiction. Utopias are wishful thinking, dystopias are dire warnings, and there is an interesting variant, let’s call it the Fauxtopia, where a utopia is introduced then gradually unmasked to reveal the dystopia lurking beneath. In Midtopia, nothing is perfect, but not everything is terrible, because the world does not revolve around you and your supposed destiny. The story moves around the three main foci of sociological fiction—the personal concerns of the characters, the public issues of their community, and the historical context that has produced both the community and the characters. With this approach, it’s rare to have a protagonist so influential that they bend the arc of history entirely around them. More often than not, the protagonists think and act in ways that won’t fit the traditional tropes and don’t lead to the usual outcomes.

In addition to my own books, there are two novels and one series that I would cite as examples of sociological fiction in midtopian settings. I wouldn’t claim that all of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books fall into this category; the earlier works in particular are very predictable in style. However, the Disc’s fantastical history and lore gradually acquire weight as the series progresses, and the books become more serious without ever losing their humour. Plots turn not only on myth and magic, but also on mundane things like law and order, journalism, diplomacy, monetary systems, communications, and transport.

Special attention is given to the development of recurring characters, which ensures that they are never mere cogs. How many authors have created a personification of Death so appealing and relatable that it’s hard to be devastated when beloved characters meet him at last? This is beautifully midtopian, acknowledging that everyone dies in the end and seeing it not as tragedy but as a natural encounter.

The second example, Tessa Gratton’s The Queens of Innis Lear, is very different in tone. Based on the King Lear myth that we best know from Shakespeare, the story has a quasihistorical context, tensions within and among ruling families, and several characters undergoing various kinds of personal crisis. These are all the ingredients for sociological fiction, but midtopian doesn’t mean boring, and Gratton never forgets the dramatic roots of the tale.

I was particularly struck by this declaration by the main female protagonist, Elia: ‘I don’t want to be chosen above all things…I want to be a part of someone’s whole.’ That is the core of the story, for both personal affairs and foreign affairs. We can’t choose just one thing to be or one person to love above all. Our loyalties and responsibilities are multiple and will sometimes conflict with each other. Whether royal or commoner, we have to find balance between our personal identities and our public roles, our dreams and our duties, not only to honour the work of those who have gone before us, but also for the sake of those who will come after.

While Discworld’s setting is fully and unmistakably fantasy, and Innis Lear is a fantasy-historical version of pre-Roman Britain, Zen Cho’s novel Black Water Sister takes place in Malaysia in the real world and the present day. However, this version of ‘real’ includes experiences which might be judged fantastical by some. Like several of the Discworld books, and like The Queens of Innis Lear, it is also about finding one’s place in a situation where the usual roadmaps do not apply, and the security of being chosen above all things is impossible or undesirable.

A young woman returns to Malaysia with her parents after almost twenty years living in the USA. She has a degree from Harvard and a girlfriend, but she is also unemployed, her parents are penniless after her father’s battle with cancer, and she absolutely cannot tell her family she’s a lesbian. She’s already struggling to re-assimilate, but her real challenge—being haunted by her grandmother’s ghost—is what vividly illustrates how the life we dare to call ours is in fact shaped by our ancestors. Whether or not we are aware of it, we are formed by the country or countries that built them and broke them, the stories they passed down to us and the secrets they kept from us, and the beliefs that inspired them and subjugated them. Family love can be a kind of haunting, a bond which even death cannot sever.

The gods are an acknowledged presence in these three fictional and real universes, but faith brings no clarity. Fate does not come with indisputable prophecies and unalterable stars. There are only risks to be weighed and choices to be made. New happenings in the present and new information about the past change the equation minute by minute so that what was dearly wished-for in the beginning can become a cup of poison at the end.

And yet, in spite of the imperfection and uncertainty of these Midtopias, we can also find warmth and connection, meaningful and rewarding work, and unlooked-for gifts and revelations. Faith in a higher power may lead to disenchantment, the hope for a better world may fade to disappointment, and a love that looks true may end in desolation… but trust, perseverance and kindness still matter, and may even be enough.

Some want fiction with comfortable tropes and predictable plots. Others prefer their stories dark and dramatic, sharp-fanged and merciless. I like Midtopia because it’s most like the real world, both dark and dramatic and filled with ordinary comforts. In my world (and my worlds) nothing is perfect but not everything is terrible, we are all somewhat chosen and no-one is chosen over all, and the ghosts of the past walk with us, seen or unseen, as we forge ahead to the future.

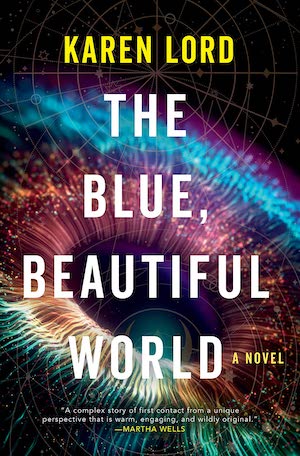

Buy the Book

The Blue Beautiful World

Barbadian writer Dr. Karen Lord is the author of Redemption in Indigo, which won the William L. Crawford Award and the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature and was nominated for the World Fantasy Award for Best Novel. Her other works include the science fiction novels The Best of All Possible Worlds and The Galaxy Game, and the crime fantasy novel Unraveling. Lord also edited the anthology New Worlds, Old Ways: Speculative Tales from the Caribbean.

Thank you for giving a name and definition to the type of SFF that I’m trying to write. No fates, no prophecies, no easily seen fake dragging of the feet. Just what happens to the character and what the character does with it based on who they are and what they desire grounded in the world around them. And it all changes as events change perspectives! Please write more of your type of book :-)

A lot of what Sheri S Tepper writes is (at least for me) “social SF”, ‘The gate to women’s country’ is a perfect example of midtopia.

And what about the Drakka series by S. M. Stirling? Ummm… John Brunner ‘Stand on Zanzibar? Neal Stephenson ‘Anathem’

Thanks for this!

You make me interested in your own work and more sure I’ll be reading Black Water Sister soon.

I think that a number of U. K. Le Guin novels — and especially novellas — are deeply anthropological as well as sociological.

Her late Earthsea novellas come to mind, as does Always Coming Home. The Dispossessed, which I just started to reread, and in a different way, The Left Hand of Darkness may have higher stakes, but are very much meditations on people in richly layered, ambiguous societies.